Persian History, Part 1 ~ by Anna Sadler

Disclaimer. We hope that there is no one to mind that we have borrowed some of the lovely pictures for this article from some of the earliest (and long out-of-print) books of the cat fancy. We will give full credit for each picture at the bottom of each photo when enlarged. Do CLICK on the thumbnails to view the full pictures!

The Persian Cat - The Beginnings

Today’s Persian is a living, playing, purring result of more than 150 years of loving, astute breeding. Over time, breeders have molded what Mother Nature gave mankind into a shared vision of beauty and serenity. These same breeders all the while maintained the balance of health and vigor with the gentle temperament that has created such a devoted following of admirers and pet owners.

On these pages, you will see pictures of many modern Persian cats in full show splendor. These glorious cats illustrate just how well generation after generation of breeders have applied their sense of artistry to the foundations laid over the last 150 years. These cats pictured look very little like the cats first identified as “Persians” in the mid 1800’s.

In the mid 1800’s, traveling diplomats began bringing longhaired kittens back from middle Eastern countries to their families in England and continental Europe. They were generally called by a name reflecting their country of origin: Persians from Persia (Iran); Angoras from Ankara (Turkey), and - though far less common -- the Russian cats. They were an instant success, especially in England, France and Italy, and were much in demand, eclipsing in popularity the native domestic cats in those countries, which had short hair. Then, as now, the beautiful long hair might have created the spark of interest, but the gentle nature cemented the relationship of people with the Persian. The history of the modern Persian would begin with these cats, though their beginnings are rooted further back in time.

Moving back through time

Prior to the period beginning in the mid 19th Century, the origins of the Persian and the other cats that would later meld into the one breed of that name, are not clear. Archaeological evidence places the domestication of the cat - or some would say, the domestication of people by the cat - at around 4000 years ago in Egypt. Sleek, shorthaired cats are depicted in art and religious artifacts of that period, and thousands were entombed as mummies. Early civilization records that the Romans introduced the domestic cat throughout Europe, and sailing ships finally carried them to the New World and later yet to Australia.

Some naturalists believe that mating between the European Wild Cat or the Pallas Cat, both of which have a longer, denser coat that evolved to protect them from harsh climates, with the earliest domestic cats, introduced the long hair into the domestic cat’s gene pool. Others believe that a genetic mutation occurred spontaneously rather than by slow evolution. In either event, the long hair was to become the hallmark and the crowning glory of the Persian.

From sought after pet to display at cat shows

The exact origins of the cats that have come to be known as Persian may forever remain muddled, but most authorities concur that longhaired cats were brought into Europe from points East. Europeans and Americans began to breed these imported longhaired cats together, selecting the traits that they found most desirable, to meet the growing demand. Cat clubs were formed to record lineages of these pets, and the natural outcome was that in July of 1871 the world’s first cat show was held in England at the Crystal Palace in London.

The exact origins of the cats that have come to be known as Persian may forever remain muddled, but most authorities concur that longhaired cats were brought into Europe from points East. Europeans and Americans began to breed these imported longhaired cats together, selecting the traits that they found most desirable, to meet the growing demand. Cat clubs were formed to record lineages of these pets, and the natural outcome was that in July of 1871 the world’s first cat show was held in England at the Crystal Palace in London.

The Father of the Cat Fancy title must undoubtedly go to English gentleman and artist Harrison Weir, who produced the first and subsequent cat shows at the Crystal Palace. He also authored a book, Our Cats and All About Them in 1889, that contained beautifully rendered drawings of the various breeds as well as a Standard of Points of Excellence that is remarkably like those still in use today.

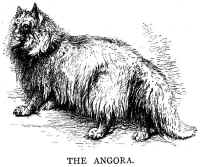

Primary breeds that were melded into the modern Persian were the Angora and what was then called the Persian. The original Angora was generally recognized to have the longer, finer, silkier hair, while the Persian was described by Weir and other early writers as having heavier boning, larger head, less pointed ears, and larger, round eyes. “It is larger in body and generally broader in the loins, and apparently stronger made, than the foregoing variety (the Angora) ...” White was the most popular color in Angoras, while black and blue were Weir’s favorites in Persians. He remarked that brown tabby was prevalent in the few Russian cats seen in England.

Primary breeds that were melded into the modern Persian were the Angora and what was then called the Persian. The original Angora was generally recognized to have the longer, finer, silkier hair, while the Persian was described by Weir and other early writers as having heavier boning, larger head, less pointed ears, and larger, round eyes. “It is larger in body and generally broader in the loins, and apparently stronger made, than the foregoing variety (the Angora) ...” White was the most popular color in Angoras, while black and blue were Weir’s favorites in Persians. He remarked that brown tabby was prevalent in the few Russian cats seen in England.

The colors of longhairs, represented in the writings and paintings, showed that the solid colored cats were preferred, and that shaded silvers and smokes were popular, and that gracing the show bench also were reds, tabbies, tortoiseshells, blue-creams and all varieties of bi-colors and calicos.

The colors of longhairs, represented in the writings and paintings, showed that the solid colored cats were preferred, and that shaded silvers and smokes were popular, and that gracing the show bench also were reds, tabbies, tortoiseshells, blue-creams and all varieties of bi-colors and calicos.

The beginnings of color genetics

Color genetics of the cat at that time were still a fascinating mystery, and the earliest books from both England and the United States include delightful flights of fancy. For instance:

“...persevering fanciers might derive interest and amusement from trying to breed out-of-the-common specimens. A black-and-white spotted like a Dalmatian hound, or a cat marked with zebra stripes, could doubtless be produced in time by careful and judicious selection.” (Frances Simpson, The Book of the Cat, 1903)

The love of beautiful cats, and the idea of showing them in competition crossed the Atlantic quickly, as did demand for longhaired cats. Helen M. Winslow, an American early cat fancy historian, said in Concerning Cats, published in 1900, that cats were not so well appreciated in France, but that there were some breeders, and there was a cat show as early as 1896 in Paris. Most of the early records show a preponderance of Angoras over Persians in France. Italy and Spain also were developing young cat fancies.

The love of beautiful cats, and the idea of showing them in competition crossed the Atlantic quickly, as did demand for longhaired cats. Helen M. Winslow, an American early cat fancy historian, said in Concerning Cats, published in 1900, that cats were not so well appreciated in France, but that there were some breeders, and there was a cat show as early as 1896 in Paris. Most of the early records show a preponderance of Angoras over Persians in France. Italy and Spain also were developing young cat fancies.

Persians cross the Atlantic

According to Winslow, the first “high-bred” longhair imported into the United States was a black, imported from Spain by Mrs. Edwin Brainard. The second came to Mrs. Clinton Locke, of Chicago, who imported Wendell, a white, brought directly to the United States from Persia, and the foundation for Lockehaven Cattery. The exact date is not given, but placed at about 1875. Frances Simpson, in The Book of the Cat, published in 1903, however, would argue, and claims that her first Persians - a pair of blue-eyed whites - were obtained in 1869 from “...a sailmaker’s pocket, from a foreign vessel, which put into a seaport town for repairs after a severe storm.”

Though some smaller cat shows had been held in New England, the United States’s first widely attended and successful show was at Madison Square Garden in New York in May, 1895, drawing 176 cats, exhibited by 125 owners “besides several ocelots, wild cats, and civets.” The shows crossed the country as quickly as the ocean, and early cat fancy activity included shows in Chicago, where numerous white Persians exhibited by Mrs. Clinton Locke and Mrs. Josiah Cratty occupied center stage.

Though some smaller cat shows had been held in New England, the United States’s first widely attended and successful show was at Madison Square Garden in New York in May, 1895, drawing 176 cats, exhibited by 125 owners “besides several ocelots, wild cats, and civets.” The shows crossed the country as quickly as the ocean, and early cat fancy activity included shows in Chicago, where numerous white Persians exhibited by Mrs. Clinton Locke and Mrs. Josiah Cratty occupied center stage.

The cat fancy helped homeless cats even in the earliest years

While the early breeders concentrated on their valuable, imported cats, they did not forget the less fortunate domestics. The cat fancy’s dedication to the welfare of all cats was evident from the very beginnings, as shows were held to benefit humane societies, and the Chicago Cat Club established a refuge for “stray, homeless, or diseased cats”.

The early cat fancy was primarily an avocation of people with adequate leisure time and financial resources. Snob appeal was important, and imported cats and their offspring were highly sought after. Winslow frequently mentions prices for cats that would have amounted to a king’s ransom in the earliest years of the 1900’s. Tootsie was “the famous cat which made $2000 for the temperance cause.” Napoleon the Great’s owner refused $4000 for him, but his progeny commanded high prices, such as Juno, a calico daughter, that sold for $1500.

The early cat fancy was primarily an avocation of people with adequate leisure time and financial resources. Snob appeal was important, and imported cats and their offspring were highly sought after. Winslow frequently mentions prices for cats that would have amounted to a king’s ransom in the earliest years of the 1900’s. Tootsie was “the famous cat which made $2000 for the temperance cause.” Napoleon the Great’s owner refused $4000 for him, but his progeny commanded high prices, such as Juno, a calico daughter, that sold for $1500.

In the United States, which had no indigenous domestic cats, another longhaired cat had made its way from northern Europe several hundred years before, by way of Viking sailing vessels. It had established a place for itself in New England, where its long, thick hair protected it from the harsh winters, and it was able to reproduce in the wild. This cat came from the common progenitors of today’s Siberian and Norwegian Forest Cat breeds. In the United States it came to be known as the Maine Cat, or Maine Coon Cat.

Winslow characterized attitudes of her era when she said “Mrs. Locke’s cats are all imported. She has sometimes purchased cats from Maine or elsewhere for people who did not care to pay the price demanded for her fine kittens, but she has never had in her own cattery any cats of American origin.” Likely some of the earliest Persian catteries did incorporate a few of these, by now, “native” longhaired cats, but that was the exception rather than the rule. The Maine cats were shown with the other Longhaired breeds in cat shows, and judged against the same standards of points. In fact, the Best in Show of the 1895 Madison Square Garden show was a neutered brown tabby Maine cat named Cosie. Within the Shorthairs, show divisions were made by breed to accommodate the domestic shorthaired cats, the Siamese, and the Manx and others that would come later. None of the early cat fancy history books make it clear why a similar division by breed was not made for Longhairs. Though the breeds were described to have different conformation, they were judged against the same basic standard of perfection, and as a result, the earliest Persians and Angoras would eventually lose their separate identities.

In fact, by 1903 when Frances Simpson wrote The Book of the Cat, she said, “...I must be pardoned if I ignore the class of cat commonly called Angora, which seems gradually to have disappeared from our midst.” Simpson then goes on to describe the cat fancy’s tendency to at that time, for show purposes, to divide cats into Longhairs (Persians), Shorthairs (domestic or English) and “Foreign” cats, which included the Siamese and Manx.

On both sides of “the pond” the Persians and Angoras were freely inter-bred, as early fanciers incorporated the most desirable traits of each breed into a single one that maintained the name “Persian”. In so doing, the Angora as a separate breed was thought to be extinct until it was rediscovered in 1962 in a breeding program in the Ankara Zoo. Only at that time was the Turkish Angora as a pure breed reestablished by importing cats into the United States from that zoo. The Persian as it originally existed became lost in the amalgamation of breeds that maintained its name.

In America: The house that Persians built

The American cat fancy basically patterned itself on the British model, though even early on the American fancy exercised its independent streak, and different methods of judging took hold. The British preferred that the exhibitors be banned from the room where judging took place, while the Americans preferred the more open, showy style, in which exhibitors and visitors were present. The first American registry (as opposed to the more social clubs) was the American Cat Club, formed in 1896 after the successful Madison Square Garden show, but it was short-lived. The Cat Fanciers Association, which was to become the largest and most successful of the registries, was formed in 1906. The success of any of the registries and shows on either side of the Atlantic was built upon the popularity of the Persian (or Longhair) cat, which both dominated entries and drew spectators.

The emphasis was on color

The earliest cat fancy was one of discovery, of refining tastes and changing fads and fashions. More emphasis in the shows was given to color and texture of fur than of any “type” or “conformation”. In Harrison Weir’s “Points, of Excellence” he assigns 20 of the possible 100 points - more than for any other feature - to color in the self-colored Longhair cats. Even more was given for tabby cats -- 15 for color and 15 for markings. Cat clubs were formed, dedicated to particular colors of cats, and very different standards evolved on that basis, even among the same breed. Some would include up to 35 points for color alone.

The world goes to war - twice!

Two world wars would have strong impact on the developing cat fancy, especially in England, as what was a hobby primarily of the idle upper class, gave way to more serious concerns. The Persian’s firm foothold in the homes and hearts of people meant that its survival was assured, though, and people shared their own meager rations with their beloved pets.

Before World War I, the established cat clubs dedicated to particular colors of longhairs, enabled members to more easily locate other breeding stock when the war years disrupted cat fancy activity. This trend of heavy emphasis on color thus was able to continue through the war years and beyond. In 1933 Evelyn Buckworth-Herne-Soame, in Cats: Long-Haired and Short, warned readers,

“In breeding pedigree cats of different colours, the first thing to remember is to mate colour to colour - cream to cream, black to black, and so on. ... Anyone owning a tortoiseshell female or queen, as we call them in the fancy, will find her a positive bundle of charms, for she produces kittens of several colors - reds, creams, blacks, and tortoise-shells - in fact, the colours contained in her own brightly patched coat. But again, her kittens must mate with studs of their own particular colour.”

The 1930s - some things remain the same, some change

The world emerged from the World War I, and the cat fancies in the United States and even in devastated Europe, began the process of rebounding. Cat shows, which had been on hiatus, once again displayed the results of fanciers’ breeding selections, and Persians again assumed center stage. Cat fancy historians again began recording the milestones.

The world emerged from the World War I, and the cat fancies in the United States and even in devastated Europe, began the process of rebounding. Cat shows, which had been on hiatus, once again displayed the results of fanciers’ breeding selections, and Persians again assumed center stage. Cat fancy historians again began recording the milestones.

In the shows of the 1930’s, each color still had its own Standard of Points, with quite different emphasis on the various elements, but with the largest designation in each being for color. It was during these years that the colorbred blue would surpass the white to attain the pinnacle of winning type that would continue for decades to come.

In the shows of the 1930’s, each color still had its own Standard of Points, with quite different emphasis on the various elements, but with the largest designation in each being for color. It was during these years that the colorbred blue would surpass the white to attain the pinnacle of winning type that would continue for decades to come.

Included in the Longhair Varieties in 1933 in England were: blacks, whites, smokes, red tabbies, red self, silver tabbies, chinchillas, blues, brown tabbies, blue-creams, tortoise-shells, creams, tortoise-shell and whites, black and whites (or magpies). Almost no mention is made during this time of the Angora as a separate breed.

In the United States between the two wars, the Maine Coon cat had fallen into disfavor because of the snob appeal of the imported longhaired breeds. Some of the Persian colors, such as bi-colors and calicos, while still bred and included in the stud books, were relegated to inferior status to the far more popular solids and shadeds. The first Himalayans had not yet been born. Cat fanciers persevered, carefully selecting their breedings, though at that time there was no antibiotic or vaccination that could save kittens from devastating disease, and fleas were such a problem in southern U.S. states that Persians there were still virtually unknown. These breeders carefully and painstakingly preserved their records, writing out pedigrees in longhand, and the registries dutifully produced the stud books as error-free as they could make them.

In the United States between the two wars, the Maine Coon cat had fallen into disfavor because of the snob appeal of the imported longhaired breeds. Some of the Persian colors, such as bi-colors and calicos, while still bred and included in the stud books, were relegated to inferior status to the far more popular solids and shadeds. The first Himalayans had not yet been born. Cat fanciers persevered, carefully selecting their breedings, though at that time there was no antibiotic or vaccination that could save kittens from devastating disease, and fleas were such a problem in southern U.S. states that Persians there were still virtually unknown. These breeders carefully and painstakingly preserved their records, writing out pedigrees in longhand, and the registries dutifully produced the stud books as error-free as they could make them.

Almost as quickly as Europe had recovered from the World War I, and the cat fancy rebounded, along came World War II, which pitted cat fanciers’ countries against one another. Daily life in England during the blitzkreig became a struggle. Even in the United States, the war effort, including shortages of gasoline, food and other supplies, as well as families being disrupted as soldiers took to the battlefield meant that the cat fancy was put on the back burner again. Cat shows took a second hiatus, and the cat fancy marked time. With its large and healthy gene pool, a result of its tremendous popularity, the Persian would emerge from the war much healthier than some of the smaller breeds, and would take up where it left off - dominating the cat show scene.